The first thing that I learned in this process was this: Use vector graphics. You will revise your text, and consequently, your word balloons so many times it will make you head spin. I admit that, when it comes to my own art, my aversion to using a computer in conjunction with my hand art is very great. At the height of my madness I thought of hand lettering and ballooning all of my text. While I still like the idea of this, to even begin to pull it off, you have to have really polished all of your text before you even begin lettering. This requires you to be well ahead of schedule on your writing, and commits you to your text when your book is not even close to compete. In the end, I found myself choosing between my own bizzare fetish and a real increase in the flexibility I could have with editing my book. I think that the path that I chose is the right one for me, and for most people who are just getting started.

Also, give some thought to altering the balloons so that they are not simply ellipses. This can easily be done with the pen tool and Bezier handles. If you don't know how to use these then read the help section of your graphics software program, I can't very well describe it here.

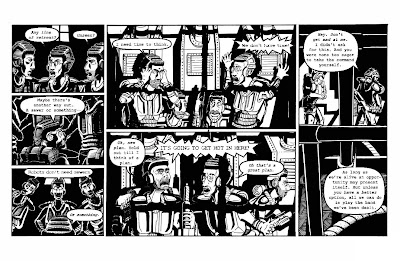

Give some thought to what your characters are saying. How big should the balloons be? Should they be thicker? Thinner? Spiky? These are all important decisions. Context is everything. Make the balloons as emotive as the characters that are saying them and make the words inside match.

Also, experiment with different fonts. Find a font that might be similar to the one you are using, but more distressed. Then you can use that font for shouting. If you make a comic about marines, in space, there could be a lot of shouting.

See the following examples here:

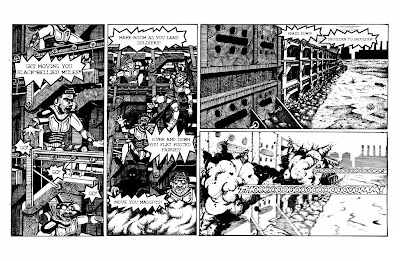

And also here:

And also here: Note that there is a place for hand lettered work, but it is usually in the tastefully placed sound effect. More on that.

Note that there is a place for hand lettered work, but it is usually in the tastefully placed sound effect. More on that.Sound effects are an excellent place to throw around your hand lettering skills. I find that the best way to go about doing this is to trace the area that they need to fill from your drawing, then do the lettering on a separate piece of paper, and finish by giving its own layer in Photoshop so that it can be properly manipulated at will. The result is lettering that blends seamlessly with your art.

I have way too many thoughts on this to contain them all in one post so we'll come back to this later. Right now I am really tired and I'm gonna go to bed early.